Templar Symbolism

One thing the armed forces and the Church have in common is a love of

symbolism, and of insignia with symbolic importance. This is true today

and was ever so, and it was so particularly in the Middle Ages. It would

hardly seem surprising, therefore if the Military Orders, who were at

once soldiers and monks, should have developed various devises to identify

themselves and to express or hint at what they stood for. Such symbols

appeared on the Templars' clothing, shields and equipment, on their flags,

on their buildings, on their tombs and in their manuscripts. The carvings

in various castle dungeons- where the last of the Templars awaited their

dark fate- also take the form of symbols and are relevant to the matter

of Templar iconography, and to what motivated the mysterious brethren.

There is much confusion and myth associated with the iconography used

by the Templars, with some symbols being popularly associated with them

that they in fact never used, and some that they did use being generally

overlooked. My intention here will be to shed some light on the matter,

and to redress some misconceptions.

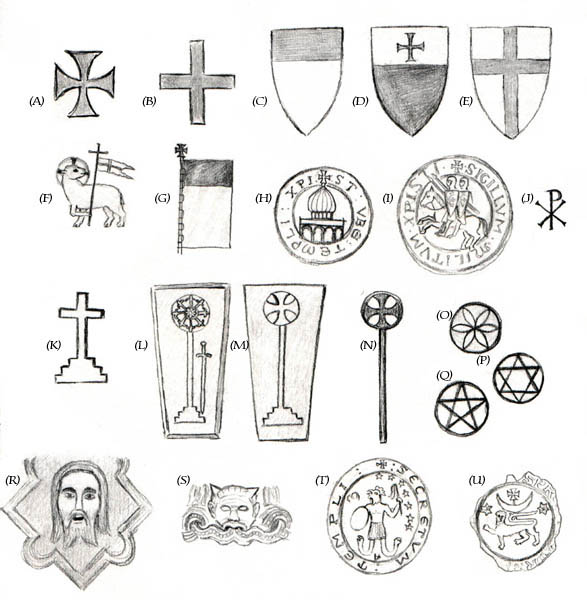

Pal Ritook, in a 1992 article entitled 'Templar Architecture in England' touched on the matter of symbolism. Ritook wondered if there was any specifically Templar iconography to be found in the decoration of Templar buildings. Ritook highlighted various problems here, particularly with correctly identifying given carvings as Templar, and being of the right date.

There seem to be a profusion of carved grotesques, 'green man' and animal

heads found in Templar churches (often forming corbels or bosses). London's

Temple Church has curious animal, human and demon heads spaced around

its internal arcade and green-man heads sprouting foliage from their mouths

above its original entrance, on the exterior. Another 'green man' head,

this one with horns, may be found on the chancel arch of Temple Garway

church (see illustration 'S'). Carved heads may also be found at Temple

Bruer and Temple Guiting, and on many Templar churches on the continent.

However, these are by no means rare on non-Templar buildings of the Romanesque

and early Gothic era. Identifying them with particular Templar ideas or

with the charges of heretical head worship is therefore difficult.

Ritook, touching on the Templar Cross, found this symbol 'regrettably

not peculiar to the Templars', and that it is difficult to distinguish

between crosses used by the Templars and other monastic communities. I

would agree with this. The croix pattee, with flaring arms of equal length,

the same type as the German 'Iron Cross' (illustration 'A') was a characteristic

symbol, but not unique to the Order, much as round churches were a characteristic

but not uniquely Templar architectural form. Pope Eugenius III granted

the Templars the privilege of wearing a red cross on their white mantles

or cloaks on the eve of the Second Crusade, but the exact type of cross

was not stipulated. Some 13th century images of Templars, for example

tomb figures from Italy, and a carving from Villasirpa, Palencia, show

the brothers in their monastic dress. They white cloaks over long, darker

coloured robes. On the left shoulder of the cloak is a simple cross with

straight arms of equal length (Greek cross- illustration 'B'). The colour

white is said to stand for purity, the red for martyrdom. Sergeants, lower

class members of the Order, must have been deemed less pure than the more

aristocratic brethren, in that case, as they wore black or brown instead.

(The Templar knights were protective about their white finery, and resented

the offshoot Order the Teutonic Knights adopting the same dress, albeit

with a black cross instead of red). The Templars themselves do not seem

to have developed a system of insignia of rank, but their Grand Master

was identified by the ceremonial staff he carried, called a baculus, which

was crapped by a cross within a disk (illustration 'N').

The Templars adopted the line from the psalms 'not unto us o lord, but

to thy name goes the glory' as their battle cry. Their war banner was

called 'beauseant', which meant piebald (two coloured) but may also have

been a deliberate play-on-words with the rousing instruction 'be fine'.

The flag was black and white (illustration 'G'). An illustration of beauseant

by the monk Matthew Paris of St Albans, in his chronicle, shows it as

being divided horizontally, with the white lower section being greater

in area than the black upper section. The black and white colours supposedly

referred to the two faces of the Order- terrible avengers to the enemies

of Christianity, gentle protectors to the faithful. Elsewhere in Paris's

work (which makes numerous references to the Templars, including their

conduct during the Seventh Crusade) a depiction of two Templar knights

shows them bearing a similar design on their shields, which are both white

below with a black upper part (illustration 'C'). The implication is that

all Templars carried this design on their shields, instead of the red

cross of St George, which is generally attributed to them (illustration

E). However, not all contemporary images agree. A Templar depicted in

a fresco in the church of San Bevignate, Perugia, Italy, is shown carrying

a shield which is black below and white above, with a small cross in the

upper section (illustration 'D'). The livery of the warhorses ridden by

other knights in the fresco echo this design. Riding in their chain-mail,

with their striking livery of black white and red, the Templars must have

been an impressive and distinctive sight in battle order. Their counterparts

the Knights Hospitaller appeared almost as their negatives, in black mantles

with white crosses (in later days the Hospitallers used the eight pointed

cross which became known as the Maltese Cross). The Hospitallers' banner

was a red flag with an ordinary white cross. Both brotherhoods were forbidden

from retreating from a battlefield while these banners flew, and if one

of the Orders' flags was lost the knights were expected to rally to the

other (unfortunately in the last days of the Crusades, relations between

the two Orders were to deteriorate).

Both Orders were devoted to the Virgin Mary and to John the Baptist, and

occasionally used the head of the latter as a symbol. The Templars also

venerated St Catherine and St George. The Lamb of God (Agnus Dei) was

another symbol favoured by both Military Orders. It represented the martyred

Christ, and sacrifice. It holds a banner bearing a cross. In London, carvings

of the lamb can be seen on St John's gate, which is all that remains of

the Hospitallers' old HQ in Clerkenwell. It can also be seen around the

Inns of Court, off the Strand, where the law society of the Middle Temple

inherited the lamb device from the Templars, along with as the premises

(which had formerly been the Templars' British HQ). The other legal society

using the site, the Inner Temple, adopted the winged horse Pegasus as

its arms, possibly taken from a badly drawn or weathered image of the

two riders.

Most important people in medieval times, including the heads of religious orders, had a personal steal. This was a mould, usually round and resembling a coin, for leaving an impression in wax or lead, which was attached to official documents for purposes of validation and authentication. The Templars' official seal was kept in a safe at their head quarters in Jerusalem, which, it is said, could only be accessed by three keys-held by the Grand Master and two high officials.

The device of two knights on a single horse was the nearest thing to an exclusively Templar symbol, which appeared on various versions of the Order's official seal (illustration 'I'). The seal was changed with minor variations for every new Grand Master. The earliest known version of the two riders motif is that of the Grand Master Bertrand de Blanchefort, dating from about 1158. The meaning of the emblem is unclear, but could refer to the dual function of the order- religious and military. It could also hint at the Templars' duty to support their needy brothers. (Templars did not actually have to share horses, and would hardly have been an effective cavalry force if they had! The rule in fact stated that each knight should have three horses, a warhorse, one for general transport and a spare.) Blanchefort's seal was encircled by Latin script reading 'Sigillum militum', on the front, with 'Christi de Templo' on the reverse (Seal of the soldiery of Christ and the Temple). A later version, the seal of Reginald de Vichier, read 'Sigillum militum xpisti'. This is unusual- the first letters of Chris's name are replaced with the Greek 'PX' (Chi-rho). This monogram was a common symbol of the Eastern Church, and was also used by the Templars (illustration 'J'). It appears several times in the decorations of the Commandery church of Montsaunes in southern France for example.

Jerusalem was the Templars' original reason for being- defending both the Crusader state and the pilgrim traffic to the holy places. They were proud of their connection with both the Holy Sepulchre (where they were consecrated) and the Temple of Solomon, (where they resided throughout most of the 12th century, between their founding soon after the First Crusade and their eviction just before the Third). A domed building frequently appears on the reverse side of the Templars' official seal, with a cross at its apex (illustration 'H'). This appears to be the Dome of the Rock Mosque, converted into a church. This building would be influential on Templar architecture.

The masters of provincial Templar Commanderies also came to issue their

own seals, incorporating various Templar symbols. The 'Agnus Dei' was

used by several Masters of England, for example and also by the Master

of Provence. Some believe that as well as its conventional interpretation

as a symbol of Christ, the 'Agnus' was chosen because of the word's relation

to the Latin 'Agnito' meaning wisdom.

The Templars were brought down amid allegations that they practiced heretical

worship of a severed head. The image of a bearded head (possibly that

of Jesus or John the Baptist) was found on a board hidden in a medieval

cottage's wall in the Templar village of Templecombe in the West Country

(illustration 'R'). Bearded heads also appear on the seals of two Templar

Masters of Germany, including one of a Bro. Widekind. However, Hospitaller

seals also show similar heads, and the Hospitallers were never accused

of unchristian worship, so it is hard to say how incriminating this evidence

is. The seals of other provincial Templar masters have been found to include

many other symbols. These include combinations of crosses and fleurs-de-lis

in various configurations, while castle towers, eagles, griffins, doves,

horses and single mounted knights are also not unknown. The star and the

crescent moon also appear. A late seal of the Templar from England shows

a lion stood below a crescent moon and a cross, between two six pointed

stars (illustration 'U'). Some have been tempted to see the moon as relating

to goddess worship or to Islamic influence, but this is pure conjecture,

it seems to me.

There is no direct evidence of the Templars using the six-pointed Star

of David (alternatively called the Seal of Solomon), now thought of primarily

as a Jewish symbol (illustration 'P'). However, it can be traced in the

plan of the round churches the order built, with six columns supporting

the central part. One such building, TempleChurch, still stands in London,

and an almost identical building once stood at the heart of the Paris

Temple, the Templars HQ in Europe. A similar six-pointed design also appears

repeatedly in the decorations of Montsaunes (illustration 'O'). It resembles

six petals within a circle, and is a symbol linked with the Cistercians,

the white monks who fostered the original Templars. As for the pentagram,

now thought of as an occult symbol, there is little evidence of the Templars

using it, although it is apparently to be found on graves at the Templar

base in Tomar in Portugal. It was also a common stonemason's mark at the

time, and the Templars were known to have had mason brethren (illustration

'Q').

Some of the abstract designs at Montsaunes may hint at the Templars having

knowledge of and interest in the Cabbala, and have been interpreted as

illustrations of the sepiroth spheres. If the Templars did have a propensity

for such mysticism, they would have had to investigate it in secret to

avoid suspicion of heresy. The issue of whether there was a secret group

within the Templars, which diverged from Catholic Orthodoxy, is for me

still an open question. An intriguing hint that this might be the case

is a seal bearing the image of the Abraxas (illustration 'T'). Around

it is the legend 'Templi Secretum.' The Abraxas is a curious image, a

warrior with a cockerel's head and snakes for legs. He holds a round shield

and a flail whip, supposedly representing wisdom and strength. Abraxas

stones were apparently used in as magical charms by the Gnostic sects

in the first centuries after Christ. ('Abraxas' may be the root of the

magic word 'Abracadabra!') Abraxas images were used by the Basilidean

sect of Alexandria, who were condemned as heretics by the early fathers

of the Catholic Church. Abraxas is said to have represented the supreme

deity, from whom emanated the angels, one of which, as the Gnostics thought,

was the flawed Jehovah who created the material world. Obviously to medieval

Catholics this would have all seemed the worst sort of heresy, and the

chimera-like image would have appeared bizarre and demonic. Whether the

Templars knew the true meaning of the Abraxas, or merely used it as a

heraldic device, is hard to assess. Clearly the majority of the Order

remained loyal to the Catholic Church, and many shed their blood in defense

of the medieval Catholic version of True Religion. There may, though,

have been an inner core, the 'Templi Secretum', that was informed by Cabbalistic,

Cathar and Gnostic ideas.

For most knights, the Order Temple offered a viable path to salvation

in warfare for Christ. It seem that belonging to the Templars meant being

separated from the world, and most knights seem to have forsaken their

secular identities, and with it their family heraldry. Belonging to the

Order was a higher honour. Many Templar graves do not carry effigies,

coats of arms or inscriptions. A device which frequently takes their place

is an elongated cross with a stepped base. Sometimes the cross reflects

the Grand Master's baculus (illustration 'M'). One such survives propped

within the porch of a later church at Newent in Gloucestershire. Sometimes,

though, the circular part at the head contains a flowery cross, with eight

arms like spokes finishing in fleurs-de-lis (illustration 'L'). Often

swords are carved alongside the cross, and sometimes tools testifying

to the craft or the deceased are also shown.

A cross with a stepped base is called a Calvary Cross (illustration 'K').

A strange thing is that in many castle dungeons where the last Templars

were imprisoned, similar Calvary Crosses can be seen carved into the walls.

It is hard to see how these prisoners could have been in contact with

each other, and it seems almost as though there was some pre-arranged

plan for the Templars to leave these carvings as a marker of their presence.

Such crosses can be seen in castles at Chinon in France, and at Warwick

and Lincoln in England. Stepped based crosses are familiar from Templar

graves, and it seem somehow fitting that the last Templars should have

carved these crosses in their bleak prisons, just as their Order itself

was dying. Perhaps they drew some comfort from them. Perhaps they identified

with Christ, martyred at Calvary in the lost Holy Land.

I have mentioned most of the symbols that there is evidence for the Templars having used. Curiously, given their association with the Temple of Solomon, they do not seem to have used the Ark of the Covenant as a symbol. This suggests that they did not find the relic, despite what some would like to think, and may never have been particularly interested in it. Likewise, despite the later myths portraying the Templars as Grail knights, the Templars do not seem to have often used the symbol of the chalice (that is unless the elongated crosses with round heads and stepped bases on the tombs can be interpreted as abstracted chalices, which is not an idea I find very convincing). So despite the Templars having common patrons with the authors of the Grail romances, there is not much evidence of links between the two.

At some of the heresy trials, the idol allegedly worshipped by the Templars

was named as Baphomet. Since the 19th century this has been associated

with the goat-headed creature dreamed up by occult fantasist Elephas Livi.

This devilish image has little similarity with any real Templar imagery.

Neo-Templar groups have also introduced imagery that the historical Templars

never seem to have used. For a start the eight-pointed cross of the Knights

of Malta is often erroneously worn where a Templar would have worn the

Greek or pattee cross. Certain symbols commonly used within freemasonic

rites have also been suggested as Templar in origin when this does not

seem to be verifiable. The skull and crossed bones, for example. I have

never been able to find a Templar artifact bearing this device. The closest

things are the 12 green man heads at TempleChurch, with four stalks of

foliage coming out of their mouths in 'X' shapes. These are badly weathered

and could at first glance be confused for the skull and crossed bones

symbol. The Templars did not use such grim imagery, though. Skulls and

bones were seldom used in Church decoration before the time of the Black

Death. It has also been alleged (by authors such as Andrew Sinclair and

Keith Laidler) that the Templars were ritually dismembered after death

and buried with their legs crossed over the torso and the head placed

above. This idea is unfounded, and, as far as I can ascertain, Templar

burial rituals were completely orthodox. (The story of the 'Skull of Sidon'

introduced into the mix during the Trials, does not seem relevant to Templar

beliefs or practices either.)

Masonic 'Knights Templar' in the US use the symbol of a Latin cross within

a crown, but the historical Templars did not use this symbol either. Neither

did they use the interlinked square and compass, (though some medieval

images do show God as the divine architect, holding compasses, and some

allegedly Templar graves appear to show set squares and what may be compasses

or shears, as well as other tools such as mallets). The Templars do not

either seem to have used the symbol of a triangle/pyramid with an eye

at the centre (so beloved of conspiracy theorists, who link it to the

'Illuminati'). The earliest examples of this 'all seeing eye' symbol,

that I can find, come from the late renaissance. They are quite common

in baroque Catholic Churches, but absent from medieval Templar ones. That

said, the pyramid-like stepped base of the Templars' calvary cross just

could be a progenitor of this image.